Introduction

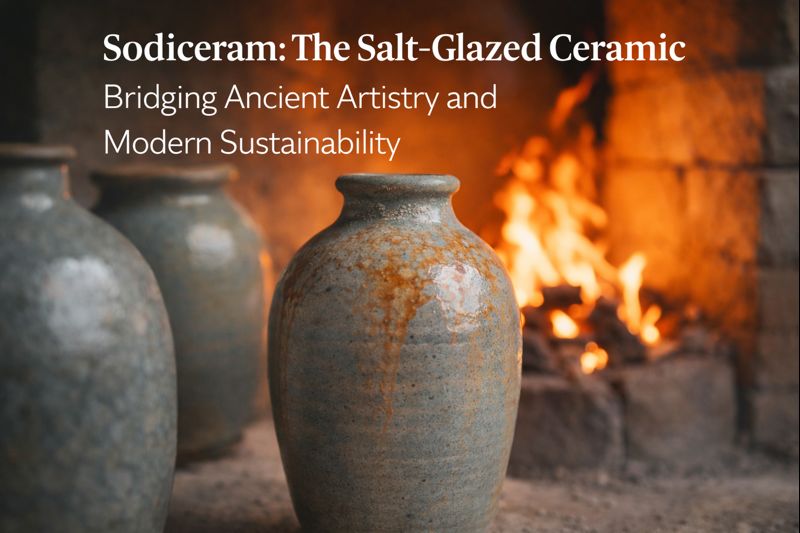

In the rich tapestry of human material culture, ceramic arts occupy a foundational thread. From the terracotta warriors of Xi’an to the exquisite porcelain of Meissen, the alchemy of earth, water, and fire has produced objects of utility and sublime beauty. Among these diverse traditions, one technique stands out for its unique, shimmering finish and its deep connection to elemental chemistry: sodiceram, more commonly known as salt-glazed pottery. This ancient method, which involves throwing common salt into the fiery heart of a kiln to create a distinctive, glassy coating, is experiencing a remarkable renaissance. Today, sodiceram represents not just a historical craft, but a compelling narrative of sustainable artistry, where a simple mineral transforms humble clay into a vitrified, durable, and breathtakingly natural object.

The origins of salt glazing are shrouded in the smoke of medieval European kilns, most notably along the Rhine River in Germany around the 14th century. Potters, seeking a solution to make their utilitarian stoneware vessels non-porous and liquid-tight without the expense of lead-based glazes, stumbled upon a spectacular accident or a moment of brilliant intuition. They discovered that when sodium chloride (NaCl) – common table salt – was introduced to a wood-fired kiln at its peak temperature (around 1300°C or 2372°F), a remarkable reaction occurred. The salt vaporized, splitting into sodium and chlorine. The sodium then combined with the silica (SiO₂) in the clay body to form a thin, glassy layer of sodium silicate—a glaze born directly from the kiln’s atmosphere. The chlorine escaped as hydrochloric acid gas, a notable and pungent byproduct. The result was a surface unlike any other: pitted with a texture often described as “orange peel,” adorned with subtle flashes of bluish flame marks, and possessing a characteristic, slightly dimpled sheen that feels cool and glassy to the touch.

This “sodiceramic” process, named for the sodium (sodic-) that is central to the reaction, quickly defined a whole category of pottery. For centuries, it was the premier method for creating robust, waterproof containers like jugs, crocks, and storage jars, famously used for spirits, pickling, and drainage pipes. Its beauty was functional and rustic, dictated by the volatile dance of flame and salt vapor. The glaze formed where the vapors touched the clay, meaning pieces shielded from the kiln’s atmosphere or resting against others developed unglazed “kissing” spots, adding to their unique, unreproducible character. Each piece bore the direct fingerprint of the firing process, a record of its position in the kiln and the path of the salty flames.

With the Industrial Revolution and the advent of cheaper, more controllable powdered glazes, the labor- and resource-intensive practice of salt glazing dwindled. Its environmental impact, particularly the emission of hydrochloric acid, also became a concern in populated areas. For a time, it seemed this ancient technique might fade into obsolescence, preserved only in museums and historical reenactments.

Yet, in recent decades, sodiceram has been powerfully reclaimed, not as a relic, but as a vessel for contemporary artistic expression and ecological philosophy. Modern artisans and ceramic artists are drawn to it for reasons that resonate deeply with today’s values.

Firstly, sodiceram is a paragon of material authenticity and process-driven art. In an age of digital perfection and mass production, salt glazing remains resolutely analog and unpredictable. The artist controls the clay body, the form, and the placement in the kiln, but the final glaze is a surrender to the elements. This collaboration with fire and chemistry yields one-of-a-kind surfaces that cannot be precisely duplicated. Contemporary artists use this to their advantage, creating sculptural forms where the glaze pools, streaks, and highlights contours in ways no brush-applied glaze can. The natural “orange peel” texture catches light dynamically, and the range of colors—from warm grays and browns to delicate blues and peaches—is achieved through mineral impurities in the clay and the specific conditions of the fire, not synthetic colorants.

Secondly, and crucially, sodiceram is being re-evaluated through a lens of sustainability. While the historical environmental concerns are valid, modern practitioners address them with innovative technology and a holistic view. Contemporary salt kilns are often designed for greater efficiency and can be fitted with sophisticated scrubbing systems that neutralize acidic emissions. More importantly, the fundamental material palette is strikingly simple: clay, water, salt, and fire. There are no commercially manufactured glazes containing lists of sometimes toxic metallic oxides. The glaze itself is made from a abundant, natural mineral. This aligns with a growing desire in craft and design for transparency, low-toxicity materials, and a deep connection to the earth. A finished sodiceram piece is extraordinarily durable, essentially a slice of artificially created geology, meant to last for millennia with minimal environmental footprint from its material sourcing.

This sustainability extends to its lifecycle. A salt-glazed pot is non-porous and inert, making it perfectly safe for storing food and drink. Its hardness makes it highly resistant to scratching and wear. In a culture grappling with disposability, a well-made sodiceram vessel is the antithesis: an heirloom object whose beauty and utility are permanent.

The aesthetic of sodiceram also speaks to modern sensibilities. Its look—organic, textured, quietly luminous—fits seamlessly into the minimalist, wabi-sabi influenced interiors that value natural materials, imperfection, and a sense of quiet history. A salt-glazed vase or platter is not loud or ornate; it is a quiet, tectonic presence that elevates a space through its tactile and visual honesty.

Furthermore, the practice itself is a form of cultural sustainability. Keeping this knowledge alive—the engineering of the kiln, the precise timing of the salting, the understanding of clay bodies—is an act of preserving human ingenuity. Workshops and ceramics programs worldwide now teach salt firing, ensuring that this flame-keeping tradition is passed to new generations who will interpret it in novel ways.

In conclusion, sodiceram is far more than a historical pottery technique. It is a living dialogue between element and artisan. From its medieval origins solving a practical problem, it has evolved into a sophisticated art form that answers contemporary calls for authenticity, sustainability, and profound beauty. It reminds us that magic—and stunning utility—can arise from the most basic ingredients: earth, water, fire, and a handful of salt. In each salt-glazed piece, we see the captured moment of transformation, a permanent record of a volatile, creative reaction. As we move towards a future that must reconcile human creation with ecological responsibility, sodiceram stands as a potent symbol. It demonstrates that enduring beauty can be forged not through complex industrial chemistry, but through a mindful and masterful partnership with the fundamental forces and minerals of our world. It is not merely ceramic; it is geology accelerated by human hands, and its quiet, glassy sheen continues to reflect the enduring power of natural alchemy.